Consumers will spend US$237 billion on online purchases in the United States alone in 2010, Javelin Strategy & Research predicts. That’s almost 15 percent more than in 2009.

Online retail is also growing globally. MasterCard announced a global agreement with cross-border e-commerce shopping firm Borderlinx in August which lets MasterCard holders purchase products online from overseas, for instance.

Meanwhile, American businesses are eying overseas markets, where there is growth potential. Apple, for example, now gets over half its revenue from international sales.

However, American companies seeking to expand their online retail sites abroad have to deal with differences in culture, process, language and laws, not to mention converting currency into U.S. dollars.

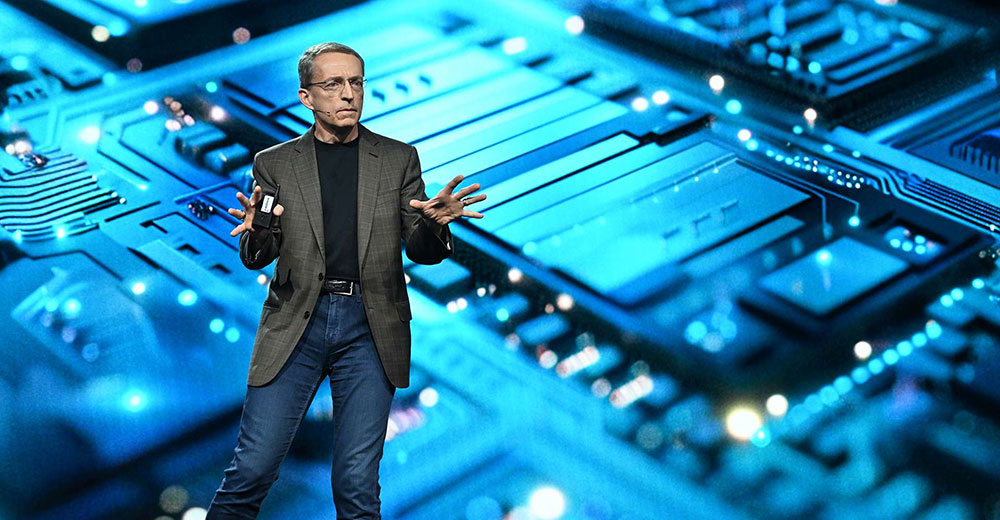

The E-Commerce Times spoke with Michael Scheib, CEO of Asknet, which offers a global e-commerce platform, about the pitfalls American businesses face when trying to do e-commerce abroad.

The E-Commerce Times: Let’s talk about some of the difficulties of doing international business for U.S. companies.

Michael Scheib:

American companies trying to expand to Europe are finding that this is not like the U.S., where there are 50 different states but there’s cultural homogeneity. If you move from, say, Germany south into Italy, for example, the Italians don’t just speak a different language; their behavior is different. Then, in Spain, the people’s behavior is completely different from that of the Italians.

It starts with eating habits — people in the southern hemisphere of Europe don’t go to a restaurant before 9 p.m. so if you go to a restaurant in Spain for dinner at 8:30 p.m. you might get a table but the cook won’t show up before 9 p.m. Rush hour is around midnight, when people turn up with their whole family, including small children, so you wonder, when do they sleep?

The answer is, they sleep in the afternoons from about 1:30 p.m. to 5 p.m. and they close their businesses down. Then they go back to work until 8 p.m. So if you want to sell them something, you start early in the morning and go until about 1:30 p.m., then between 4:30 p.m. and 8 p.m.

If you go to France, it would be very impolite if someone invites you to drink a bottle of wine at lunch and you say you prefer water; you won’t make a sale to him. Two people drink one bottle for lunch, three people drink two bottles. Then they go back to work but do their emails, so don’t expect too good responses during this time.

ECT: Could a company upset its foreign distributors when it goes online? How can companies best deal with that?

Scheib:

Why are companies setting up originally in different countries? To localize software and deliver customer support and other support to their clients and prepare appropriate marketing material. For this purpose, their local distributors get a 40 to 50 percent resale discount. Now, if you go online suddenly, the distributors would earn less from this kind of business.

This means that any kind of software vendor, for example, needs to think deeply about converting his channel strategy into an online strategy. You can’t just set up an online store in France or Germany or anywhere else as a U.S.-based company and expect customers to flock in. You may be cannibalizing your channel, so don’t expect that the channel will contribute much to the future such as trying to expand your markets or handling complaints.

You must make sure that the channel is compensated accordingly. This is a rather big issue, and we offer business consulting to clients and help them resolve these business to business issues.

ECT: Are there any special government regulations U.S. businesses may need to know about when doing business online abroad?

Scheib:

“Generally no, except in some of the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) countries.

For example, if you go into Brazil, you have to consider that it’s not easy to get money out of the country if customers are paying in the local currency and you don’t have your own subsidiary in Brazil.

In China, you have to consider issues with Google.

Generally speaking, in the main countries where commerce is rather well-known, there are tax implications you have to consider — in the U.S. there are different tax rates in different states, and this is very much relative to the B2B business.

You also have to consider that total buying habits are different. I think this is even more important than government regulations and laws.

Soft regulations are also more important than government laws. For example, you can’t have an English website or English shopping cart in a foreign country if you want to be successful. This is also the case for all of southern and eastern Europe, but it’s not so much an issue for Scandinavia where they speak good English.

ECT: What other points would you raise to U.S. companies seeking to do business online overseas?

Scheib:

Start with the language — shopping carts and websites should be localized. We help clients localize shopping carts in 38 languages, for example.

Next, even if you have a site 100 percent perfectly translated into another language, people abroad might still not be able to follow the workflow correctly, and that’s when they need a customer service number they can call where they can speak to someone in their own language. We offer customer services in 16 languages.

Also, and this is important for Internet sales, you must remember that an Internet shop is open 24 hours a day, and customer service should be available all day as well. Someone may want to shop at 2 a.m. and they may want to call for help.

Let’s continue. If you buy something online in North America you use your credit or debit card. In Germany, people prefer to have the money transferred from their bank account to the merchant, so you must consider that.

In Russia, they use mobile payment methods where they pay via their mobile service. In Japan, people pay for software in supermarkets, which give them an authorization number they input into their PCs to complete their transaction. In China, people go to fuel stations to buy software and get the authorization code. Fuel stations are everywhere in China, supermarkets are not.

We have set up 33 different globally accepted payment options and are working on more.

ECT: What advice would you give about formulating a global social media policy?

Scheib:

At the moment we have not had either a good or a bad experience with social media like Facebook. We have even looked into it; there’s a lot of discussions around software products in this space, but the companies we are working with have not been so far talked a lot about in the social media.

We have a lot of employees who use social media a lot and we noticed that they’re talking much more about themselves and their problems than B2B issues.

Social Media

See all Social Media