Ask any security practitioner about ransomware nowadays, and chances are good you’ll get an earful. Recent outbreaks like Petya and WannaCry have left organizations around the world reeling, and statistics show that ransomware is on the rise generally.

For example, 62 percent of participants surveyed for ISACA’s recent “Global State of Cybersecurity” survey experienced a ransomware attack in 2016, and 53 percent had a formal process to deal with it. While ransomware is already a big deal, it is set to become an even bigger deal down the road.

One of the questions organizations ask is what steps they can take to keep themselves protected. Specifically, what can organizations do to make sure that their organization is prepared, protected and resilient in the face of an outbreak?

A strategy that can work successfully is the long-tested “tabletop exercise” — that is, conducting a carefully crafted simulation (in this case, a ransomware situation) to test organizational response processes and validate that all critical elements are accounted for during planning.

This strategy works particularly well for ransomware because it encourages direct, frank and open discussions about a key area that is often a point of contention during an incident: the ransom itself.

What Is a Tabletop Exercise?

Invariably, in the context of an actual ransomware incident, someone will suggest paying the ransom. Sometimes it’s a business team that sees the ransom as a small price to pay to get critical activities back on track. In other cases, it might be executives who are eager to defer what is likely to be a long and protracted disruption to operations. Either way, paying the ransom can seem compelling when the pressure is on and adrenaline is high.

However, most law enforcement and security professionals agree that there are potential downsides to paying the ransom. First, there is the possibility that attackers won’t honor their end of the deal. A victim might pay them but lose its data anyway. Even if the attacker should follow through, there is the danger of creating a perception that the organization is a soft touch, which could induce attackers to retarget it down the road.

An organization might make a decision when feeling ransomware pressure that it would not make when thinking it through calmly in the abstract. That is why working through the issues ahead of time can be valuable.

The exercise prompts discussions about these topics and fosters calm and rational decision-making. Further, it helps familiarize critical personnel with response procedures, pre-empting “hair on fire” behavior if an actual crisis should occur.

Ransomware is only one area where a tabletop exercise can provide value. In fact, many aspects of an organization’s security posture can be tested in this way. An organization can employ tabletops to examine everything from business continuity to disaster preparedness to distributed attacks, using a structure tabletop exercise. It’s also possible to test general response communication channels for unplanned situations with no explicit response procedures established — for example, the kidnapping of key personnel traveling abroad.

Fighting in the War Room

Assuming that an organization wants to use this method, what’s the best way to set it up? The process isn’t difficult, but there are a few things to keep in mind. A few critical elements can separate a useful, productive event from a less-than-valuable one.

First, take time to fully bake the exercise plan. It should be based on something that actually could happen to your organization. Leverage areas that you might be concerned about, areas that participants will be familiar with from the news or outside sources (such as ransomware), or areas where you suspect you have potential issues.

Create a scenario that is plausible, that contains components that play out over time (for example, in response to actions that the participants may or may not take) and that is complex enough to give all participants a way to engage. Note that you may not wish to share all information with all participants — one of the things you may wish to test is communication pathways, so it’s in bounds to expect participants to communicate between themselves.

As you develop your plan, keep in mind that the one of the goals should be immersion: You want the participants to feel like there is something on the line as the exercise unfolds. Bits of realism can add significant value here. For example, depending on the exercise you’re planning, you could use simulated screen captures, snippets of prerecorded audio or video (such as a reporter behind a desk conducting a news report), an on-camera interview with a key executive, etc. There’s no need to break the bank to do this: You simply want to add enough verisimilitude to get people hot under the collar and feel like there’s something actually happening.

Likewise, enlist participation from all levels of the organization, including — and in particular — senior leadership. Leaving key stakeholders or decision-makers out (for example, excluding a highly placed executive because of availability limitations or level of interest) can detract significantly from the value of the exercise.

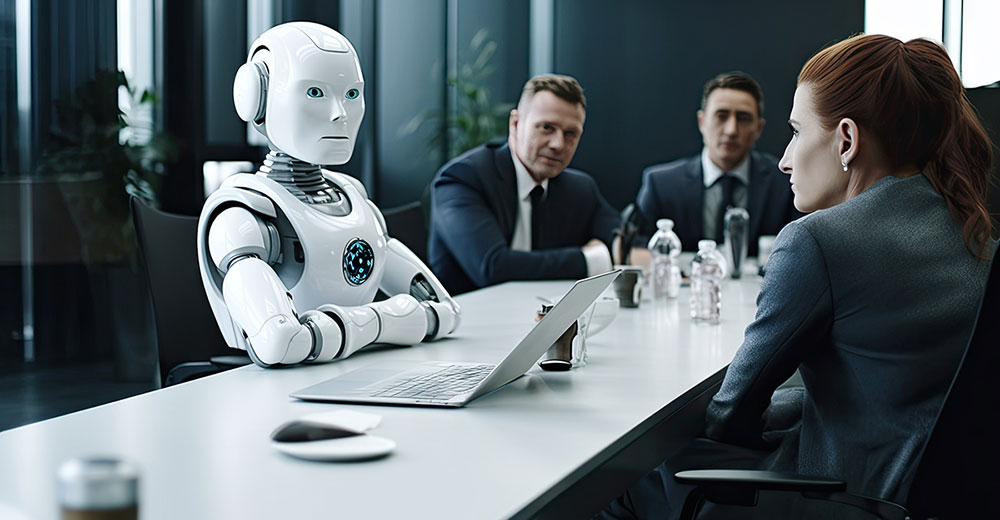

Counterbalance the urge to cast too wide a net, though, as physical proximity to the exercise can be valuable, too. Having all the players in one room during the exercise can lead to conversations that wouldn’t happen otherwise. A useful technique is to set up a “war room,” or central meeting place where you can have everyone together to conduct open discussions.

Last, deliberately introduce elements that ramp up the adrenaline in the room. It may sound strange, but to some degree you actually want to cultivate some heat — that is, exchanges that might be contentious between participants. Why? Because a disagreement that happens during the exercise (and can be worked through there) is a disagreement that won’t happen when an actual event transpires.

A tabletop exercise can be a great way to hone your security response capabilities and make an incident (should it occur) much more manageable than otherwise would be the case. By planning through responses, by testing methods for information sharing and communication, and by getting disagreements out of the way in advance, the tabletop can be both an important and a fun way to improve your organization’s security posture.

Social Media

See all Social Media